In Argentina, the best way to maintain popularity is to stay out of government. It is far easier to score points either by criticizing the incumbent's shortcomings or simply by avoiding the inevitable taint governments suffer when they try to manage a society polarized into powerful competing interests. The Argentines are notoriously impatient, even amnesiac, when it comes to politics. Government popularity quickly erodes . . .

|

| Arturo Illia |

Coups in Argentina have always emerged from a murky amalgam of dissatisfaction and conspiracy, but the 28 June 1966 overthrow of President Arturo Illia is the least explicable of all. Illia was neither engaged in the senile abuse of power, like Yrigoyen, nor intent on subjugating Argentina to his personality, like Perón. He was not poised to impose a successor by electoral fraud, like Castillo in 1943, nor had his party just been defeated by the Peronists, like Frondizi's in 1962. Chaos and terror did not grip the country, as in 1976. Economic growth averaged 9.7 percent per year in 1964 and 1965. Yes, there were problems: an annual inflation rate of over 20 percent (a rate that would later appear rather quaint) and an organized "battle plan" of strikes and factory occupations. But here was no subversion, no rampant corruption, no perilous threat to the fatherland or its constitutional order. The nation's problems were not those that beg for military solutions at the sacrifice of constitutional norms. For these reasons the military takeover of 1966 is sometimes called the frivolous coup. . . .

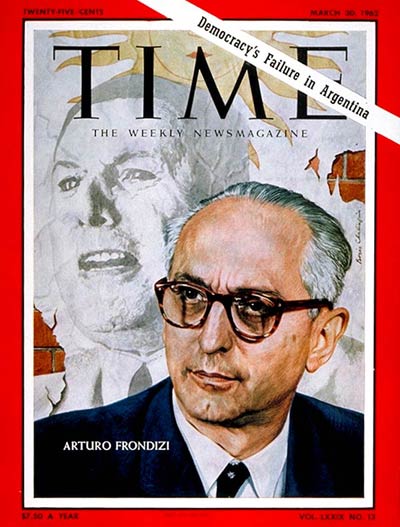

It is now convenient to forget how enthusiastically the people welcomed the military when it took over in March 1976. Official ineptitude, an insidious terrorism from both right and left, and rampant inflation left the government of Isabel Perón with few friends. Some political party leaders, including longtime Radical Ricardo Balbín, half-heartedly entered last minute negotiations to try to form a multiparty coalition that could save civilian rule. But it was too late. Order had to be restored; the military seemed the natural candidate for the job. The faded scruples against military intervention in civilian politics seemed trivial in that dire hour. The coup brought a collective sign of relief, and was supported by such notable civilians as former president Arturo Frondizi and newspaper editor Jacobo Timerman.

|

| Raúl Alfonsín |

. . . how could constitutional democracy reappear in 1983? By default. Alfonsín's victory was not arduously won against tyrannical force. The armed forces, discredited by the debacles in the Malvinas and the economy, retreated to the barracks and left the government behind them like a spent shell. (The struggle against subversion did not fatally compromise the military's public support; but for its other failures the military might still be in power.) Elections were the only alternative; everything else had failed. Into this political wasteland moved Raúl Alfonsín, seeking the presidency and the vitalization of Argentina's supine democracy.